For most, the works “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience” will forever be linked to the poet William Blake, but to beat-based musicians, producers and legions of jazz-funk fans, they’re the influential first two solo albums by Los Angeles producer, composer and arranger David Axelrod.

The Los Angeles native died Sunday at 83, leaving behind a body of work whose soulful grooves, grand string arrangements and meticulous melodies continue to reverberate in some of the hip-hop era’s biggest hits, most notably Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg’s “The Next Episode.”

Axelrod’s death was confirmed by his wife Terri Axelrod through their longtime friend Eothen Alapatt. No cause of death was given.

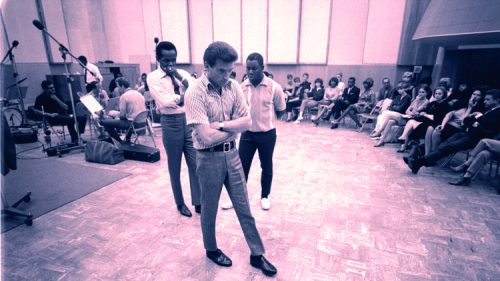

A singular Los Angeles musical figure, Axelrod got his first taste of success in the early 1960s as an A&R man for Capitol Records. His devotion to rhythm and blues helped guide production on hits for soul singer Lou Rawls, jazz saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley — most notably “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” — and a few strange psychedelic albums for the Electric Prunes.

As he did so, Axelrod, whose primary instrument was drums, mastered increasingly sophisticated, stereophonic studios that allowed for grand experiments. The best of that work can be found on “The Edge: David Axelrod at Capitol Records, 1966-1970.”

He further explored his ideas on those first two solo albums, which were inspired by Blake’s two volumes of poetry. Instead of language, though, Axelrod probed the duality by employing instrumental music driven by precisely miked, expertly played drums, crisp, clear bass tones and melodies that clung like barbs.

“See, I love the bass,” Axelrod told The Times during a long 2007 feature. “The first I usually put down on the score pad is the bass line. Then I work from there.”

With that bass, he composed expansive structures that reflected late 1960s and ‘70s Los Angeles while mostly ignoring the hippie vibe happening on the Sunset Strip. He created with freedom earned from Rawls and Adderley royalties.

Asked by Alapatt in an interview for Big Daddy magazine about that success, Axelrod said, “Are you kidding me? I’m golden boy! I’m the Oscar de la Hoya of Capitol Records! I could do anything I wanted to do. I was rich — making the equivalent of $700,000 a year!”

But he wasn’t interested in commercial pop. Rather, Axelrod was on a jazz and soul tip, one absorbed during a youth spent in South Central Los Angeles.

By all accounts a fascinating conversationalist, Axelrod recalled exploring the city as a teen in the 1950s in search of musical inspiration. “We rolled through all these clubs, like the Million Dollar Theatre. They would get all these R&B acts and the big bands. They’d run a picture and then they had the live acts.”

Added Axelrod to The Times of one particular curve of Crenshaw Boulevard: “Some nights there would be jazz and some nights there would be rhythm and blues — at the same room. People are always talking about Chicago, but we had that right here.”

Axelrod was hardly a hit maker, though, and jumped from label to label across the 1970s to an increasingly ambivalent public. But those beats and bass lines were too funky to ignore. A decade later, rap producers began sampling elements of his music — and they still do.

Among those whose work includes Axelrod productions are A Tribe Called Quest, DJ Shadow, Schoolboy Q, Wu-Tang Clan, Mac Miller, Lil Wayne, Eminem, Earl Sweatshirt, Common and dozens of others.

“It was kind of jazzy and psychedelic all in one,” the Los Angeles producer Madlib, who has harnessed Axelrod’s sounds on a number of tracks, told The Times in 2007 of his first encounter with Axelrod’s music. “Then there’s that funky, hard bass and drum — Carol Kaye and Earl Palmer. It was like world street music. I think it was so out there because, well, he was probably so out there.”

In that same feature, the late drummer Earl Palmer said: “His writing was very, very strange and abstract. So you had to really concentrate. There were these strange chords, and he’d put them in what seemed to be strange places, until you heard them.”

For his part, Axelrod, who was never known to hide his opinions, was less concerned about the kudos.

“I’d just like to get paid for what I’ve done,” he said in an undated interview republished on his website. “I’m one of the ten most sampled artists there is. [Paul McCartney’s publishing company] MPL alone has 89 samples and… I can’t stand McCartney. Let me tell you, he’s touring here. I should go to see him just so as I can throw a … grapefruit at him.”

Axelrod never followed through on the threat, but no matter. Much of the composer’s work is available for download and through the major streaming services, and scrolling through his catalog is a lesson in the durability of great music — regardless of whether a Beatle is involved.